All you need is a camera that allows you to manually adjust the shutter speed and f-stop. A lot of point-and-shoot pocket sized cameras do not have this feature, but many do, so check your manual. All digital SLR's allow for manual control. If your camera has a removable lens, it is 99% likely that it is an SLR. If your camera is a relatively recent model, yet is too big to fit in your pocket, it likely allows for manual control. Again, check your manual if you're not sure.

Now, on to the good stuff...

When you take a picture, there are three variables that come into play. Like planets aligning, these three variables have to combine in the right way for the picture to be properly exposed (meaning, not too dark or too light). However, there is no one perfect combination, as you'll soon discover. If you adjust one variable in one direction, you can compensate by adjusting one of the other two in the opposite direction and the result will be an equally properly exposed photograph.

The three variables are:

- ISO - How sensitive the chip in your camera is to light

- Shutter Speed - The speed at which the shutter opens and closes again to allow light to briefly pass through and hit the sensor.

- F-Stop - The size of the aperture (hole) that the light goes through when passing through the lens.

ISO

Don't worry about what it stands for. It doesn't matter. ISO can be adjusted on most digital cameras, even ones without manual controls. It is simply a measurement of how sensitive the sensor is to light, and it is something that is not fixed and can be adjusted in any digital camera. ISO is measured in hundreds, with the most popular minimum being ISO 100, used mostly for bright sunlight or other very bright areas. The most popular maximum is probably ISO 3200. This is much more sensitive to light, and is most suitable for dimly lit indoor shoots. You can have any range of numbers inbetween, but the most common settings in most cameras are ISO 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 and sometimes 3200. As you may have guessed, each one is twice as sensitive (or half, if you're going the other way) as the number before it. Thus if you set your camera for ISO 200, it is twice as sensitive to light than if you set it at ISO 100. In photography, whenever something is twice/half as much as the one before it, it is called a stop. Thus, ISO 200 is one stop higher than ISO 100. ISO 800 is three stops (400, 200, 100) higher than ISO 100.

So why does this matter? Well ideally you want to use the lowest ISO possible, because it simply looks better. As you up the ISO on your camera, it is just like turning up the Gain on a guitar amplifier. As you artificially amplify the sound, you start to hear static. Well in a camera, as you artificially amplify the light levels, random specks of nastiness show up in your picture. This is called noise, and is generally something to be avoided. High ISO also tampers with sharpness, saturation, color fidelity, and the general overall quality of the image. So why not shoot in ISO 100 all the time? Because usually we don't have the luxury of being in environments that are sufficiently well-lit to allow us to do that. Sure, you CAN set the ISO to 100 while taking pictures in your living room of your christmas party, but the shutter will have to be open for much longer, leaving you with very blurry pictures as all your party guests move around in the second or two the shutter is open. Instead, you'll have to bump up the ISO to 800 or 1600 (or use a flash). The result will be a bit noisier, but at least you'll be able to distinguish faces instead of getting blurry streaks of light.

A general guidelines for ISO useage is as follows:

* ISO 100/200 - Bright, sunny outdoors

* ISO 400 - Not so sunny outdoors

* ISO 800 - Twilight or well-lit interiors

* ISO 1600/3200 - Dimly lit interiors

One minor exception worth noting. A lot of night time landscapes and city skyline shots are shot in ISO 100 or 200. Why? Because landscapes and buildings don't move, so you can put the camera on a tripod, leave the shutter open for 30 seconds or whatever it takes and you get a nicely exposed night time image with none of the noise caused by high ISO's.

Tip: If you're just starting out with manual controls, leave the ISO to Auto and focus on the other two variables below.

Shutter Speed

Shutter speed is pretty simple. It determines the amount of time that light is allowed to hit the sensor. When you take a picture, the shutter in your camera opens for a fraction of a second to let the light through, and immediately shuts again. The length of time the shutter is open determines whether you "freeze" the action in an image or "show motion" by allowing some blur. Your camera may have shutter speed options like 60, 125, or 500, but what this really mean is 1/60th of a second, 1/125th of a second, and 1/500th of a second. They just nix the fraction notation to save space and simplify things. If you see something like 1" or 2", that means one full second or two full seconds. Remember there's a big difference between setting your shutter speed to 10 and setting it to 10".

Unless you have something specific in mind, you should try not to shoot at anything slower than 1/60th of a second. Anything slower than that, and you'll likely get camera shake which is sort of self explanatory. Your picture will be blurry not because your subject moved, but because you couldn't hold the camera steady in the time the shutter was open. Holding the camera steady at speeds like 1/30 or 1/15 is possible, but not easy. Don't risk it if you don't have to.

A good rule of thumb is to keep your shutter speed at 1/x, where x is the focal length of your lens. If you're shooting with an SLR camera, you'll notice the lens has numbers on top that can range anywhere from 18 to 70 millimeters (and much more, but this is most common). This is called the focal length and is a much better way of determining the magnificiation of a lens than the arbitrary 3X or 10X measurement that the beginner cameras flaunt. So for example, if you're shooting at a magnification of 100mm, you shouldn't shoot at a shutter speed slower than 1/100th of a second. Any slower could cause camera shake in your picture. If you don't have an SLR, and you don't understand any of this paragraph, ignore it. It's not vital.

Any sport action shots you see where an athlete or a ball is suspended in mid air was shot with a high shutter speed of probably 1/500 or faster.

Any shots you see where the headlights of cars seem to form a path down a road were likely shot with a slow shutter speed of one full second or more.

Aperture

The word aperture just means 'hole'. In the photography universe, it refers to the hole in the lens that allows light to pass through. However, the size of the hole is measured in something called f-stops. This is where it gets a little confusing, because the smaller the f-stop, the larger the hole. Like ISO, f-stops are generally used in increments of one stop, but the pattern is something you have to memorize.

f/1.4

f/2

f/2.8

f/4

f/5.6

f/8

f/11

f/16

f/22

f/32

Unless my memory has failed me, each of those allows twice as much light as the number that follows. Thus f/2.8 allows twice as much light through than f/4. And f/11 allows half the light that f/8 would. Like I said, the smaller the number, the larger the hole. So f/1.8 is a very wide open aperture and allows a ton of light through the lens (thus allowing you to shoot at a faster shutter speed, a lower ISO, or both). f/32 is slightly larger than a pinhole.

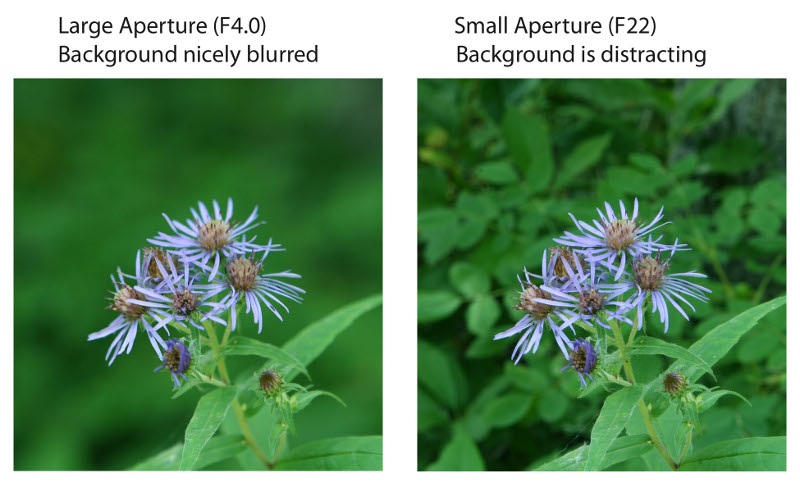

But for every benefit, there is a consequence. In the case of adjusting aperture, we are adjusting depth of field. Depth of field refers to the range of distance within the picture that is in focus. Imagine you are taking a picture of a boy standing by the Hudson River, with the New York skyline behind him in the distance. You focus on the boys eyes (as you always should in portraits).

If you shoot this picture at f/4, the boys entire face will likely be in focus, New York will be a vague but distinguishable blur.

If you shoot this picture at f/16, not only will the boy be in focus, but so will the skyline several hundred feet behind him. This is called deep or sharp depth of field.

If you shoot this picture at f/1.8, his eyes may be in focus, but his nose and ears, because they are slightly behind and slightly in front of his eyes, won't be. The background will probably be a grey and blue blob of building and sky. This would be called shallow depth of field.

As the size of your aperture gets smaller, you allow greater distance to be in focus, which may or may not be what you're looking for. Sports photographs and portraits often use very shallow depth of field to isolate the subject from a distracting background. On the other hand, many landscape photographers use high f-stop numbers like f/16 or f/22 to ensure that every aspect of their landscape, near and far, is in sharp focus. It all depends on what look you are trying to achieve.

Putting it all together

Like I said, these three variables have to be in perfect balance to achieve a picture that isn't too dark or too light. So if you are shooting a portrait of your dog on a bright sunny day with the aperture "wide open" at f/2, you'll have to lower the ISO probably down as low as your camera can go, and ramp up the shutter speed to avoid getting a picture that is too bright. Conversely if you're shooting a dimly lit wedding ceremony, you'll have to have your ISO at least at 800, and your aperture as wide as it goes to allow your shutter speed to be at a reasonable setting where you can still freeze action.

However, remember that there is more than one way to expose every picture. Shooting at 1/60th of a second, you may get a perfect exposure at ISO 400 at f/5.6. But if you wanted a little less depth of field, you could lower the f-stop to f/2 (which would be two stops) and raise the ISO by two stops to ISO 1600. As long as you keep the three variables in balance, you will get a properly exposed image.

*I later realized after reading this over, that there's a mistake in that last paragraph. However, I won't tell you what it is. See if you can figure it out yourself, and you'll know you have a pretty good understanding of the dynamics of photo exposure.

The best way to get the hang of this is to practice. And if you don't feel like practicing with your camera at home, I can reccomend a great site that will allow you to see exactly how everything I just talked about affects a picture. Check out the SimCam to test out the effects of aperture and shutter speed for yourself.

Thanks for reading, and I hope this will help you to better understand how to handle your camera. Don't let the 'auto' mode do the thinking for you!

See my own work at johngallino.com

What a well-written explanation! Good job. (It may even get me to stray past from the "automatic settings."

ReplyDelete